WORDS BY JAY NAJEEAH

Originally published in issue 001 of Film Club 3000, available to read here.

In the early 1940s, Spencer Williams, a screenwriter and actor, took the first stab at the genre we know today as “Black Horror” with the film Son of Ingagi, directed by Richard C. Khan. Though directed by a white man, it featured an all-black cast and made a statement regarding the kind of work that was missing from the canon. It would be over two decades later in 1968 that we saw another Horror film with a black lead grace the big screen with 1968’s Night of the Living Dead. Following this film, the era of Blaxploitation created a pleth- ora of misrepresentations of the Black image that were directed by white men, with films like Abar, the First Black Superman (Dir. Frank Packard, 1974), Dr. Boss Nigger (Dir. Jack Arnold, 1975), & The Bad Bunch (Dir. Greydon Clark, 1973). With rare exceptions popping up like Ganja & Hess Directed by Bill Gun in 1973, there was a major disparity regarding works with “true” representations of blackness on screen. Even with films like the original Candyman (1992), Def by Temptation (1990), Ragdoll (1999), and The People Under the Stairs (1991) debuting well after the Blaxploitation era, we wouldn’t see a Black Auteur in the horror genre reach critical acclaim until 2017’s hit, Get Out, directed by Jordan Peele. This film’s buzz led to a flood of Black Horror films and shows led by Black artists in the genre and began further to uphold the concept of auteur theory in Black Cinema.

Auteur theory is exemplified in the films of Jordan Peele & Nia DaCosta who have breathed new life into the horror genre through their understanding of classic horror tropes, film and art history, and their personal aesthetic choices in their films. I intend to talk specifically about facets of Nia DaCosta’s film, Candyman as a groundbreaker in the genre, in a post-Get Out society, as well as being a transformative piece regarding our collective reckoning with trauma.

Going in chronological order, we’ll begin with Get Out (2017), written & directed by Jordan Peele. Peele can be attributed with reigniting the social interest in what we now call Black Horror with this directorial debut. The film follows the story of Chris, a Black photographer, dating a white woman, Rose, as he prepares to meet her parents for the first time. Taking an increasingly dark, and anxiety-inducing spin on the 1967 classic Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Get Out, peers into the dangers of white liberalism at its highest degree of severity. We dig into stereotypes, implicit racism, and the commodification of the Black body and experience through this narrative feature.

Reaching critical acclaim and astounding box-office success, Get Out had a 4.5 million dollar budget and box-office earnings of 255.4 million dollars. Because of this success, we have to pose the question: what made this work? There is a compound answer for this. On one hand, accord- ing to the UCLA Hollywood Diversity reports of 2023, African-American viewership has consis- tently been “responsible for the majority of open- ing weekend, domestic, ticket sales” of films in theaters, coming in as high as 69%, of the minority share. With this fact, compounded with Jordan Peele’s mastery of horror’s cinematic language to discuss the fear that comeswith existing in a black reality, it’s only logical that this film that is representative of Black fears and realities in a way that isn’t harmful to its target audience was a bloc buster success.

Due in part to Peele’s success, there’s space to talk in-depth about the state of Black horror. To step into that conversation, I’ll use Nia DaCosta’s hit film, Candyman, which hit theaters in 2021. Written by Jordan Peele, Win Rosenfeld (a long- time collaborator of Peele), and Nia DaCosta, the story stands as a direct sequel, and what I’d like to call a continuation, of the original 1992 film of the same name. With a 25 million dollar budget, the film did well, earning 77 million at the box office. Returning to the same ideas that I mentioned regarding Peele’s films, we can also analyze DaCosta’s work. One of the most impressive things about this narrative feature isn’t just the phenomenal horror aspects, but DaCosta’s grasp on her directorial aesthetics. As a direct sequel to the original film, there are expectations and questions about how to continue such a beloved and intense lore. DaCosta, as the director, goes a creative and unexpected route for the film by blending the original framework of the fran- chise (the descent into mania & the history of trauma in a community), Shadow Puppetry, & social commentary on gentrification and the meaning of art and artists in our current society.

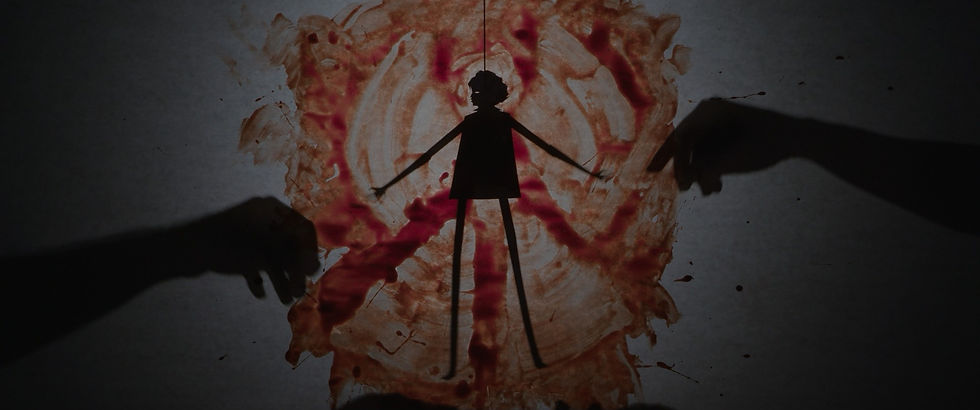

Throughout the film, we are met with shadow puppets made from cutout paper. A storytelling device as old as the stories themselves,

the use of puppetry to enrich the story of the Candyman and of Cabrini-Green is indicative of the nature of storytelling within tight-knit communities. Every time a story or a piece of lore is bought into the narrative, we are met with that pale white background and black shadows roaming across it. Like many folktales and urban legends that are shared generationally through the oral tradition, the use of shadow puppets, with maestro-like hands that we can see throughout the film is indicative of the fact that these stories morph and change as time goes on. The ownership of them is of a community, not of one person, and that’s what truly allows Candyman to continue to be iconic, even after a 29-year break between films. To be able to make the intangible fear and folklore tangible through literal pieces of paper is an extremely impressive feat. Making that feat even more impressive, and speaking to DaCosta’s ability as an auteur filmmaker, is that this feat is compounded with her using the tried and true tools of the horror genre as a tool

to discuss the cyclical nature of trauma. Starting subtly, we watch the characters muse about gentrification, white supremacy, the over-policing of disenfranchised communities, and how art affects these worlds. These musings at the opening of the narrative bud into the roots of what this film truly is about, the trauma imbedded in history, and how unless unpacked and resolved, it will continue to repeat itself and destroy everything around it. Even without the fantastic puppet work, we see this theme play itself out in Anthony’s Bee Sting being ignored until his actual hand is cut off, Colman Domingo’s character of William Burke being both a worker in a laundromat and delivering the iconic monologue about the stain on the community, which goes as follows:

“When something leaves a stain, even if you wash it out, it’s still there. You can feel it.

Uh, uh... a thinning, deep in the fabric. This neighborhood got caught in a loop. The shit got stained in the exact same spot over and over until it finally rotted from the inside out! They tore down our homes so they could move back in. We need Candyman, ‘cause this time, he’ll be killing their fathers, their babies, their sisters. I knew it was only a mat- ter of time before the baby came back here in perfect symmetry. A chance for Candyman to take back what’s rightfully his.”

We see black folks put a name to their traumas, reckon with their history, racial or otherwise, and begin to unpack the emotions that come with that.

This monologue, placed near the end of the film, brings us back to the point previously mentioned. If not dealt with, the trauma of the past will come back to haunt and physically harm us. This concept isn’t new, however. In most waves of “Black film,” not just the horror genre, we see black folks put a name to their traumas, reckon with their history, racial or otherwise, and begin to unpack the emotions that come with that. In these dealings with trauma, it is often marginalized groups who have to find and create their own spaces to make sense of their history.

No one better than Black Women can make sense of these concepts, as supported by ‘Black Women as Cultural Readers’, written by Jacquline Bobo. She states “When a person comes to view a film, he/she does not leave his/her histories, whether social, cultural, economic, racial, or sexual at the door. An audience from a marginalized group has an oppositional stance as they partici- pate in mainstream media.” (p. 96). In this context, the viewer of a film like Candyman, which was largely viewed by a Black audience, was able to

see a humanizing iteration of traumas likely felt within their own communities, all directed by a member of their community (DaCosta).

This point can be made again through the b-plot of the story. Teyonah Parris’ character, Brianna Cartwright, the partner to our lead, Anthony, has a plethora of trauma coming into the film and leaves with more as we head out. Having witnessed the suicide of her artist father (who presumably was mentally ill) at an extremely young age and choosing not to deal with that trauma as an adult and now working art dealer, she has doomed herself to repeat the cycle with Anthony as she is left stuck to watch his mental descent until his death. This fact, compounded with Anthony’s death being at the hands of racist police violence, stamps another moment where traumas of the past, in this case, the trauma of police being historically violent with Black folk, are indicative of issues not worked through coming back to haunt us. Unresolved trauma and history will always leave a stain that can’t be washed out or ignored. The stain will grow until that’s all we’re able to see.

These concepts discussed by Nia DaCosta throughout the film are part of a framework that many Black creatives have long since taken hold of to use for their own stories. Jordan Peele says it best in the foreword of the anthology series ‘Out There Screaming’ that he edited, “I view horror as a catharsis through entertainment. It’s a way to work through your deepest pain and fear–but for Black people that isn’t possible, and for many years wasn’t pos- sible, without the stories being told in the first place.” Having an outlet to share your experi- ence and not be further traumatized by it, was not a privilege people of the African Diaspora often had. With works of what we now call Black Horror, we are able to make greater sense of our experiences and release ourselves from the grip they have on us.

This idea isn’t exclusive to Black Auteurs but has consistently shown itself in the work. Horror has always displayed the fears and anxieties of a people, but Black Horror specifically uses the medium to make sense of what plagues our nightmares.

Opmerkingen